- Home

- Norvin Pallas

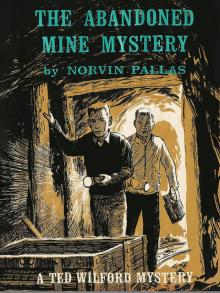

The Abandoned Mine Mystery

The Abandoned Mine Mystery Read online

THE ABANDONED MINE MYSTERY

A Ted Wilford Mystery

by NORVIN PALLAS

Table of Contents

THE ABANDONED MINE MYSTERY

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

DEDICATION

CHAPTER 1.

CHAPTER 2.

CHAPTER 3.

CHAPTER 4.

CHAPTER 5.

CHAPTER 6.

CHAPTER 7.

CHAPTER 8.

CHAPTER 9.

CHAPTER 10.

CHAPTER 11.

CHAPTER 12.

CHAPTER 13.

CHAPTER 14.

CHAPTER 15.

CHAPTER 16.

COPYRIGHT INFORMATION

Copyright © 1965 by Norvin Pallas.

All rights reserved.

Published by Wildside Press LLC.

wildsidepress.com | bcmystery.com

DEDICATION

To:

Charles, Judy, William, Nancy, and Cindy Lou

CHAPTER 1.

The Disappearing Children

AT least it wasn’t an anonymous letter. It was signed by someone named Mrs. Allen, and gave an address in East Walton. If the signature was authentic, the writer deserved consideration.

Ted Wilford, having read the letter, handed it back to Christopher Dobson, editor of the semi-weekly Forestdale Town Crier. If Mr. Dobson had saved this letter just to show to him, Ted had a pretty good idea what he had in mind.

Mr. Dobson tapped thoughtfully on the desk with his pencil. “What do you know about matters in East Walton, Ted?”

“Only that the coal mine there shut down almost four years ago, following an explosion. Until I read this letter, I had no idea there was any doubt that it was an accident Mrs. Allen seems to think it was deliberately set off.”

“Yes, but she doesn’t say who she thinks was responsible. With her husband unemployed and the family on relief, she must be bitter. But why did she keep quiet for four years? And even if the explosion closed the mine, what is keeping it closed?”

“Isn’t it the popularity of other fuels, plus the need for automation so they could compete with other people’s mines?”

Those are the reasons usually given, Ted, but Mrs. Allen hints something more is involved in this case. Naturally I wouldn’t expect you to solve an explosion that happened years ago, no doubt thoroughly investigated at the time and probably an accident anyway—” He was talking about a trip, just as Ted had hoped. “But there may be a story here just the same. What is keeping the mine closed, is there any hope of getting it open again, and what are people in East Walton doing about it? A story about a community hard hit by the closing of its chief industry might make a good feature, even though it doesn’t justify blazing headlines. How soon will you be ready to leave?”

“Right away. I’m just about caught up with everything here, and I think we could make it to East Walton by dark.”

“I take it Nelson could go with you?”

Ted grinned. “It’s his car, so it’s often a case of his going with me or else I don’t go. But I expect he’ll be glad to go.”

“Tell him to take his camera along. A few pictures to go with your story might be useful.”

“How long shall I take on it?” asked Ted, rising to leave.

“Whatever time it takes, Ted. You understand your duties here, and you’ll know what’s going on up there. It’ll be up to you to decide between them. One thing more, Ted,” said Mr. Dobson, stopping him. “You know we have our own correspondent up there—Phil Royce. It’s only a part-time thing with him, but your going into his territory makes a rather touchy situation. Better talk to him first thing, and explain matters. Good luck, Ted.”

It didn’t take long for Ted to get hold of Nelson, like Ted home from college for the summer. They packed their suitcases hurriedly, left notes for their families, and within half an hour were on the road to East Walton.

“I don’t know what I’d do without you,” Ted told Nelson as they pulled out of Forestdale.

“You’d hire a car in East Walton, and drive around in style.”

“I wouldn’t dare put anything like that on my expense account,” Ted assured him. “So you are good for something, my boy.”

“Thanks for nothing,” Nelson answered. “And speaking of work, I guess that working in a coal mine would be just about the worst kind of job. I’d rather go into orbit than do it.”

“I can’t say I’d exactly love it myself, but why so sure?”

“It’s hard work, it’s dirty, and it’s dangerous. But I wouldn’t mind that so much as the fact that it’s spooky. Just think of working the day shift during the winter. You would go to work before dawn and come home after sunset, and never see the sun at all. You might just as well live in the Arctic.”

“Where do the spooks come in?” asked Ted with a laugh.

“Well, just imagine those long dark tunnels, and your lamp throwing big shadows on the walls. You’re wandering through there all alone, and your light goes out—it’s black—not like night outside with the stars and maybe the moon, or clouds reflecting a little light. But absolutely black! You can’t see anything at all.”

“You don’t have to go into the mine if you don’t want to,” Ted remarked.

“Then you are planning to go in?” asked Nelson.

“Probably. But it’s up to you whether you go along.”

“Oh, I’ll go with you, Ted. Might as well live dangerously. Though I suppose it’s not really very dangerous,” he went on. “It would be quite a coincidence if there was a bad accident on the day and at the place where we happened to be investigating another accident. If the mine is closed, I suppose there’s even less chance of an accident than normally.”

Ted understood Nelson well enough to know that he was stimulated by danger. Though he was often bored with daily routine, he rose to a challenge like a trout to a fly. There was no better person to depend on in an emergency. Not that Ted had any particular apprehension about danger, even though he had teased Nelson a little about it. Bad accidents were extremely rare, and what could happen just visiting a colliery?

“Of course they did have that bad explosion there,” Nelson mused. “If we had happened to visit there that day, things would have been pretty rough. Just how bad was that accident, Ted?”

“Don’t ask me! Four years ago I was more interested in the latest baseball scores than I was in a mine explosion—as long as it didn’t happen to anyone I knew. I don’t believe it was as bad as it could have been, though. The explosion came while the men were changing shifts, so there weren’t many workers down there at the moment.”

“Wise me up on the mathematics, Ted,” said Nelson. “Since they’ve already had a bad explosion, does that mean they are less likely to have another one, or more likely?”

“I don’t see how it could be less likely—unless the explosion made some kind of readjustment we don’t know about,” Ted explained. “You never use up your probability. If you have just won a sweepstakes, and then buy a new ticket, your chance of winning is just as good as the next fellow’s. But something—something unknown—caused that last explosion, and the same cause might still be at work. I’d say there’s a better-than-average chance it will happen again.”

“Thanks,” said Nelson gloomily. “You’ve brightened my whole day.”

Nothing more was said about danger, and they rode in silence until Nelson remarked casually:

“I’ve got a riddle for you, Ted. Where’s West Walton?”

“West of East Walton, I suppose. Where else could it be?”

“Wrong! Take a look at the map.”

Ted took the map from the glove compartment

, and studied it for a moment. “I don’t see it on the map.”

“Right. There’s no such place. So why do they call it East Walton, if there isn’t any Walton, or West Walton?”

“Maybe there is a West Walton, but it’s too little to put on the map.”

“That’s a pretty definitive map, Ted. And you’ll notice that East Walton is on the east bank of the river. Therefore, if there were a West Walton, it would have to be on the other side of the river.”

“So . . . ?” asked Ted, realizing that Nelson must have studied the map before they started out.

“Well, do you see any roads on the map, just across the river from East Walton?”

“No,” Ted acknowledged, “but there might be small roads the map doesn’t show.”

“If there were any way to get through there, the map would show it. So if there is a West Walton, it must be terribly small.”

Nelson leaned over to switch on the radio. His pushbutton tuning was adjusted for the stations around Forestdale, so he didn’t use it now.

“See if you can find East Walton for us, Ted,” Nelson requested.

“Why? You want to come in on the beam?”

“Do I have to tell you how to do your work? Isn’t it a good idea to find out everything you can about the community you’re going into? East Walton doesn’t have its own newspaper, or a TV station, so the radio is your best bet.”

“That’s using your noggin, Nel, old boy. No one can tell me you don’t have it upstairs, no matter what everybody else says.”

Ted had no idea where to find the East Walton station, but fiddled with the dial for some time trying to locate it. When they were nearly there, he figured that the loudest station might well be East Walton, and he left it on while he waited for station identification.

“What’s on your own program, Ted?” Nelson inquired. “There are so many places you could start, I’m interested to see what the boy wonder will choose.”

Ted laughed. “I don’t have to choose. Mr. Dobson made it perfectly clear to me. The first thing to do after we’re settled in is to look up Phil Royce, our correspondent there. I’m invading his territory, and I’m supposed to get on his good side.”

“If he thinks you’re an invader, there might not be a good side as far as you’re concerned,” Nelson pointed out. “How do they work that, Ted? You’re not exactly stealing the bread out of his mouth, are you?”

“Hardly that. He works on space rates like I did when I was high-school correspondent for the Town Crier. And you know that nobody gets rich on space rates. He probably thinks of it as extra change in his pocket, and some weeks he may have doubts that it’s worth the trouble. If you turn in a dozen items, and the paper only uses one, you only get paid for the one that’s used, and the rest of your work is wasted. After a while you sort of give up and stop trying so hard. You want to be sure a story is really worth it before you even stir yourself to go after it. Mr. Dobson prefers to pay a salary, but of course he can’t afford it with correspondents so far away from Forestdale.”

“Then you don’t expect trouble with Phil?”

“Not about money. To handle a big story he’d have to put in a lot of work, and at space rates he might not feel it’s worth it. But he might take it as criticism that he overlooked a good local story, or that he isn’t handling the situation properly. I know that’s how I might feel.”

Station identification on the radio interrupted them, and it was followed by a news résumé. The national news was reported first, but nothing startling had occurred since the last news summary they had heard. Then the announcer took up local items. Suddenly they really began to listen.

“Mrs. John Llewellyn has reported to the police that her two children are missing. They set out early this afternoon searching for their pet mule, Alice, and nothing has been heard of the two children or the animal since then. The little girl, Joyce, is nine years old and blond. Her brother Johnny is seven years old, and a little darker. Both children were wearing blouses, jeans, and sneakers when last seen. They did not have hats or coats. Anyone seeing the children or the mule is requested to call the police or this station.”

“Hope they find them,” Nelson commented. “It’s a good thing it’s not cold out. That helps.”

Ted partly turned and stared out the rear window. “Beautiful sunset,” he observed.

“What about it?”

“Lots of clouds. It’s close to dark, and may rain before very long. I hope those kids aren’t in real trouble.”

He looked around at the wild rolling hills and the empty woods. There were lots of places where the Llewellyn youngsters could have got lost.

They crossed the river and turned northward toward East Walton. Though Ted had never been here before, he realized that they must be getting very close to the coal mine.

“Hey!” he shouted.

“What’s up?” Nelson demanded. Then he realized that Ted wanted him to stop, and he pulled over to the side of the road.

“What do you see up there?” asked Ted. “Aren’t those two children?”

Nelson stared. “Two people, anyway. It’s hard to tell whether they’re children or not, from down here. Take it easy, Ted. Those Llewellyn children aren’t the only kids in the world.”

“No, but they’re the ones we’re worrying about right now. Look what they’re doing. They’re gone now.”

“Where did they go?”

“I think that’s the entrance to the mine. I’ve read a little about that mine, and it’s a regular labyrinth inside. Come on, let’s go.”

CHAPTER 2.

Night In a Mine

IT was a long, steep climb over barren clay soil till they reached the entrance of the mine.

“I wonder how those kids made it,” Nelson speculated, as he slipped and went down on his hands, but quickly righted himself and struggled onward.

“Probably they didn’t come this way. They may have followed the ridge of the hills.”

“What about Alice? You think she could have made it? I know mules go down the Grand Canyon, but I don’t think that’s as slippery as this.”

“Well, we didn’t see Alice. She may not have come this way at all.”

“But the kids did, and that must mean they thought she came this way.” Apparently Nelson had accepted the fact that they were following the Llewellyn children.

They reached the entrance to the mine, and paused to look around. The entrance had been boarded up at one time, but the boards had rotted or been broken off. They doubted this was the main entrance to the mine, for there were no facilities for unloading coal or checking in workers. That was probably down at a lower level and invisible from where they stood.

A sign read:

DANGER—NO TRESPASSING

“We don’t have any choice, do we, Ted?” asked Nelson.

“No, I guess not.”

Once inside they took a dozen steps, then paused once more to allow their eyes to adjust to the gloom. The daylight from the entrance stretched ahead down the corridor, appearing ever more feeble. There was no sign of the children, but there was a turn a little way ahead of them. No doubt Joyce and Johnny—if it was they—had made the turn and were now in the darker, deeper portions of the mine.

Nelson switched on his flashlight, and the beam was feeble enough in the dim glow of daylight. But after they had made the turn, the light seemed stronger and they proceeded more confidently. Looking back they could see a patch of light at the turning, and that was all.

Though he kept the beam aimed mostly at the ground, Nelson occasionally flashed it around the walls. They did not seem to be made of coal. Evidently there had been no mining here—this was merely a corridor cut to reach the seams of coal. Their way led gradually downhill. So far, though there was still no sign of the children, they could not have gone wrong, for there were no branches off the corridor.

“Think that roof will hold up?” asked Nelson, turning the light momentarily on the ceiling o

f the tunnel.

“It’s been there a good many decades. I hope it’s good for another hour or two. I don’t think we’re in any trouble about air, either. There seems to be a draft through here. It’s possible that this is an air tunnel, built to carry air down to the lower portions of the mine.”

“Wouldn’t a tunnel like that be vertical?”

“Maybe, unless this is a double-purpose tunnel.”

“Then I suppose the bigger the tunnel the more air you get, and the bigger the tunnel the more likely it is to collapse. How do you decide what to do?”

“I guess it’s a good idea to know what you’re doing.”

They made another turn, and now had lost all touch with the daylight. The walls were beginning to take on a darker hue, as though this were nearing the main lode or vein. How far they had come along the corridor they did not try to guess, but estimated that they were some thirty to fifty feet lower than the entrance. The slope was quite steep, possibly too steep for railway cars, and anyway there was no sign of tracks.

The walls grew progressively blacker, and suddenly they had to make a decision. The corridor branched off in two directions. Apparently this was the point where the mining had begun.

“Which way do we go, Ted?”

“I don’t know. Do you think those kids could have a light?”

“They must have. How could they have come this far without one?”

“We never saw a flicker, and they couldn’t have been very far ahead of us.” He hesitated, indecisive. “Let’s try calling.”

“OK, but maybe they don’t want to hear.” However, as Ted began to call, “Joyce, Johnny,” Nelson joined him. It was a weird sound, though. The calls seemed to echo and reverberate, so that it was impossible to tell from which direction the sound came, or even to recognize the voice of the person calling.

Then they waited silently for a minute or two, hoping for an answer, but none came.

“Probably scared them half to death,” Nelson muttered, “if they even heard us.”

“If they’re within quarter of a mile of us, they heard us,” said Ted grimly.

The Counterfeit Mystery

The Counterfeit Mystery The Mystery of Rainbow Gulch

The Mystery of Rainbow Gulch The Abandoned Mine Mystery

The Abandoned Mine Mystery